Ryan Field

Freq. 122.9

Freq. 122.9

Ryan Field is a private airfield owned by the RAF thanks to the generous donation of Ben and Butchie Ryan. Located about a mile southeast of West Glacier, MT, it appears on the Great Falls Sectional as 2MT1.

Prior to arrival, each pilot is required to request and acknowledge the current safety briefing, updated annually. If you are not yet an Airfield Guide user, you will need to create a free account. The RAF requires the electronic record that you received the briefing. It is valid only for the pilot making the request.

Ryan Field – as all backcountry – is for recreational enjoyment, not training. Please no touch and goes. Land, stretch your legs, have a picnic, and enjoy the area! If you'd like to pitch your tent or reserve a camping cabin, even better!

Please sign our Visitor Log in the kiosk!

2020 Ryan Barn Raising

The Ryan Barn Story

General Information

What's Available at Ryan Field?

View the Weather Station Info for onsite weather info throughout the flying season. Text A to 406-223-8069 for current transcribed info; M for METAR.

West Side of Runway

- Tie-down spots – Bring your own rope

- 24’ x 30' shelter with wood cookstove and firewood. Potable water is available during flying season. (Fire extinguisher and emergency instructions posted on wall)

- Outdoor stone BBQ with grill

- Picnic tables

- RAF fire ring, firewood

- Tent camping sites

- Horseshoe pit with shoes; Corn hole game

- Vault toilet and primitive shower enclosure

- Cabins 3 and 4, hard sided camping cabins

- Bear boxes

- No electricity on the West side

East Side of Runway

- Tie-down spots – Bring your own rope

- Cabin for volunteer Ryan Field Caretaker, on site during flying season

- Cabins 1 and 2, hard sided camping cabins

- Bear boxes

- Ryan Barn, plumbed restrooms on south side, available 24/7

- Adirondack chairs for your use

- Fire ring, firewood

Camping at Ryan Field

To preserve a backcountry environment, Ryan Field is available for airplane camping only. Vehicular and RV camping is not allowed.

This is bear country – Unless in use, all food, garbage, and personal care items must be stored in nearby steel bear boxes. Attractants cause habituated bears, a danger to humans, and lethal for the animal. Carry bear spray, and know how to use it when hiking and berry picking.

Fires – Wood in the pilot shelter is cut short for the cook stove. Use other wood for the fire ring. No other camp fires are allowed.

Garbage – You must take your garbage with you. Please pack it in, pack it out.

Cell Service – There is limited cell coverage.

Hiking trails – Maps are located in the kiosk and pilot shelter.

Courtesy Car – RAF volunteers use donations to maintain the courtesy car, available during flying season on a first-come, first-served basis. Key and sign-out book located in the Visitor Log mailbox. Please only use the car for short trips to town and return within two hours, full of gas. Due to USFS logging on the road into Ryan Field, the RAF is limiting courtesy car use to necessary short-term travel.

Ryan Camper Cabins

The four hard-sided camping cabins are intended for RAF Supporters flying in to Ryan Field. No drive in traffic is allowed to use the cabins or camp at Ryan Field. Become a supporter here. It’s these donations that help keep the cabins open to pilots and free to use.

Each cabin sleeps up to four, for up to three nights. Bring your sleeping pad / bag and pillow. Please don't cook or keep food in the cabins, and please pack it in, pack it out.

Below is the cabin reservation calendar. To make a reservation, please complete this form. Your reservation will not be valid until you receive a confirmation email. If you have any questions, contact ryancabins@theraf.org.

Unless prior arrangements are made, we will hold your cabin until 7:00 pm MDT after which your cabin will be given to the next person. If you're traveling with others, please reserve each cabin individually rather than as a group.

The RAF appreciates usage information, so, please sign our Visitor Log.

The RAF has significant expenses operating and maintaining Ryan Field, like property taxes, insurance, and runway care. If you enjoy your stay, please consider a tax-deductible donation to the RAF. You’ll find secure orange boxes in the pilot shelter, kiosk, and barn. You may donate by check, online, or you may use provided envelopes for cash. We appreciate it! If donations exceed needs, they will be used to further the RAF mission.

Ben Ryan Autobiography

Early Years

I was born in Belleflower, California in 1923. My father was an oilfield worker and wildcatter. Mother graduated from college at age seventeen with an engineering degree from Penn State University. Teaching was her first career but much later, she went into the contracting business. At one time was the only woman in California to hold a license as a Class A General Engineering Contractor.

I have one sister five years older. She retired as a Department Head at the University of South Carolina and still lives there. I also have a half brother living in Texas. He is considerably younger than me. He was a helicopter pilot in Vietnam, despite the fact that he did not graduate from high school.

My family moved to Three Forks, Montana in the summer of 1931 where my father drilled a wildcat well that turned up dry. It was his norm to roughneck it in the oil fields until he earned enough money to finance another wildcat well.

I was introduced to airplanes in the summer of ’32 or’33. Two airplanes landed on the airfield at the north edge of town. The arrival of the planes attracted most of the town’s boys. Because I was the smallest boy, the pilot of the twin Lockheed boosted me up on his shoulder to retrieve the mail pouch from the nose baggage compartment. This was a one-time event for Three Forks.

The family moved to Livingston in 1936 where my father drilled several wildcat wells southeast of town and worked as a roughneck in other oil fields. All his wildcat wells were dry, but I did pan an ounce of gold out of the drill cuttings. I graduated from high school in 1940. I worked on oil wells until the fall of ’41, when I entered Stanford University. My sister had gone to college there, and Stanford had a good geology school. If you were in the petroleum-engineering program, the university waived the required foreign language courses, which at that time would have been in German.

Military Years

While I was at Stanford, I enlisted in the Army Reserve for training as an aviation cadet. In May of 1943, the Army called me to active duty. A year later, after finishing my advanced training at Williams air base near Phoenix, I earned my wings. The Army, for publicity reasons, flew my mother (then a WAC corporal) out from Los Angeles to pin on my wings. I was surprised to see her on the stage and I was the first graduate to get my wings, ahead of all the others. No other graduate received this special treatment. Apparently, this was written up in the LA papers and afterward I received several letters from young ladies whom I had never met.

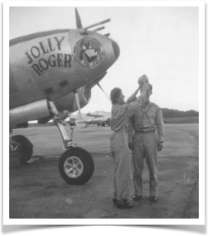

I joined the 32nd Fighter Squadron in September 1944, flying on patrol from the Canal Zone. The planes were already in Panama. Each squadron consisted of eighteen planes, four echelons of four planes each plus planes for Commanding Officer and Operations officer. We flew P-39s until the following spring when we changed to the P-38. The P-39 was very light on the controls and a joy to fly on the deck. But with its high wing loading, it was a dog above 15,000’. The P-38 was fast and very maneuverable. Its only drawback was its tendency to tuck under in a high-speed dive. The plane was red lined at 450 miles per hour. I named my P-38 the “Jolly Roger” and this was painted on the forward side of the fuselage.

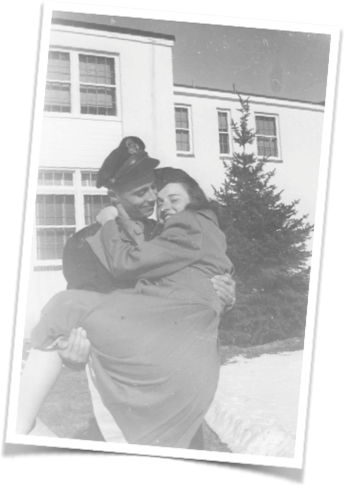

In August, 1945, I met a cute little Army nurse on a blind date. Her name was Agnes Butchkosky, affectionately known as “Butchie.” She was on a hospital ship that was broken down in the Panama Canal for several weeks. Butchie grew up near Hazelton, PA and did nursing work in New York City hospitals before enlisting in the Army Nurse Corps. After a nine-month courtship, we were married in Denver in June 8, 1946.

The most memorable day of my Army flying career occurred on Columbus Day, 1945. On that day I was assigned ground duty - Officer of the Guard. About noon the Operations Officer called to have me report to the flight line. Another officer would take over the ground-duty. The flight mission was to intercept a VIP plane and escort it to the Canal. When we flew back to the field about mid-afternoon at the end of the mission, another squadron was in the process of landing. The CO put our squadron in trail formation (follow the leader). The number two plane had a runaway prop. When this happens, the prop goes into flat pitch and forward speed rapidly falls off. I barely slid under the plane, but one of the other P-38s took my right vertical off with his left wing as he evaded the plane with the runaway prop. My plane was left with no rudder or elevator control. The next fifteen seconds seemed to be in slow motion. I was surprised at the physical effort it took to exit the diving plane. As I slid head first off the wing, I watched the horizontal stabilizer and wondered if I would go over or under it. I went under it, popped the chute and looked down to watch my plane descend. There was a circle of foam on the ocean below me where the plane had already splashed in.

After landing in the water, my life raft would not inflate. Here I had been sitting on this thing in the plane for something like four hundred hours, with the CO2 cartridge digging into my thigh. Just when I needed it, it would not work. As it turned out, I was not far from shore, and a native came out in his boat and pulled me out of the water. The Army had a standard offer to the natives of a fifty-dollar reward for any flyer they happened to save. Shortly afterward, an Army boat appeared, and I transferred to that craft for the ride back to the base. About 6:00 pm when I reached the dock, an Army doctor was waiting to check me out. He gave me some special medicine known as a Scotch. I found out later that all the ground crew at the base watched my plane go in the drink and each crew chief hoped it was his plane, as he would then be rotated back to the States.

Since I was not injured, early the next morning they had me back in a P-38 for a formation flight. It was uneventful until a hydraulic failure forced me to lower the landing gear by hand.

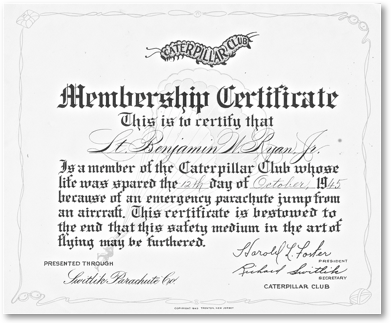

Shown below is the certificate that was awarded to Ben by the Switlik Parachute Company of Trenton, NJ when he survived his October 12, 1945 ordeal of bailing out of the P-38. It certifies his membership in the elite "Caterpillar Club." Only pilots who survive an emergency parachute jump from an aircraft are eligible.

Post-War Years

I rotated back to the States about Christmas of 1946. In March I was terminally discharged from the Army and married Butchie in Denver as she was stationed at the Fitzsimons Hospital there. The wedding took place in the hospital chapel. As I was still in the Army, the honeymoon was limited to only thirty-six hours. That summer I worked on an oil well in the Livingston, Montana area.

That fall I returned to Stanford with my new bride, Butchie. Stanford had converted an Army hospital into rooms and apartments for married couples. It was home for the next three years. Butchie worked the three to eleven p.m. shift in the Palo Alto Hospital, giving me time for uninterrupted study. My post Army grades showed a marked improvement. All of us veterans were driven to get good grades to enable us to get good jobs upon graduation. In lieu of a thesis, I instructed in the 1949 summer geology course in the field. My degree was in petroleum engineering.

I joined Richfield Oil Company as a geologist in September 1949. Richfield had just made two large discoveries in the Cuyama Valley about fifty miles south of Bakersfield. The Company had two geologists checking the wildcat and step-out wells. The geologist that was leaving the company took me out and showed me the well locations and how to describe and check the drill cuttings and cores. After returning to Bakersfield, I was supposed to return to Cuyama with the other geologist for further indoctrination. Instead, he was hospitalized with polio, and I was on my own. Normally there is a geologist assigned to each well or at the most, two wells. It turned out that I ended up monitoring four wells. The next few months were hectic.

In 1952 the Company transferred me to the new Casper, Wyoming office to take over exploration developments in the Mountain States. I particularly enjoyed mapping the geology of the mountains west of Cody. The geology was fascinating and I really liked the fieldwork. I was able to spend two summer seasons in the field.

The Company sent us to Caracas, Venezuela in 1956. In 1958 I checked a well that the Company, with others, was drilling in the Gulf of Paria. Upon returning to Caracas, I noticed a different atmosphere. The dictator had been ousted. To avoid all the fighting that was still going on, the cab driver took a round about route to the apartment and for this he got a healthy tip. Butchie had seen the convoy of the ousted President as he left the country.

In 1960 we transferred to Los Angeles. I renewed my passport and got the shots for an intended company transfer to South Africa. Instead, I spent a year working out of the LA office trouble-shooting wherever needed. Once I was sent up to Anchorage for a few days in the winter to resolve a problem. All my clothes were intended for warm climates as we were expected to go Africa next. Returning to Los Angles wearing a Palm Beach suit, I boarded a Northwest Airlines that had originated in Tokyo. When the plane reached Seattle, I was made to go through customs with all the Tokyo passengers, as no one would believe that anyone wearing such clothes would have got on the plane in Anchorage in the winter.

We were transferred to Anchorage, Alaska in 1962. With two of my fellow employees we purchased a low-time Cessna 172, which we flew until 1966 when I left the Company after it merged with Atlantic. I had an exploration crew working on the North Slope. One day I received a well written, right-to-the-point report from the party chief that they had found very promising oil sands formations along the Sagavanirktok River, south of Prudhoe Bay and that the Company should get on this right away. I wrote on the report “I concur” and sent it on to the home office in LA. Before long, men and material were moving north into what became the Prudhoe Bay oil field.

Montana

After the Richfield merger with Atlantic Oil Company was announced in 1965, we bought a step-van so we could move our belongings if we did not like the resulting company. When the company volunteered to move our possessions south, I converted the van to a motor home. While driving through the Flathead Valley in Montana in the fall of 1966, we were shown the timber-covered property where we now live, about a mile southeast of West Glacier. We liked it and made an offer that was accepted. We spent the winter touring the U.S. However, when we passed through the area on our travels that winter, we noted that there was three to four feet of snow on the ground. That is when we started to make plans for an A-frame house that would hold our belongings and become our new home.

On April 1, 1967, we parked our van at the State Highway Department gravel pit a half mile south of U.S. Highway 2 and hiked the one and a half miles on an old logging road to our new property, searching for a suitable building location. We settled on the site we still use today, mostly for its availability to water and “easy access”. We hired a local Hungry Horse, MT contractor to dig the basement and improve the road. He recommended a mason to lay up the concrete blocks and I was the “mud man”.

In May, the house lumber was delivered to the gravel pit. In order to get the 36’ long beams we wanted for the A-frame, we had to have them shipped in from Oregon. A local trucker moved the material from the gravel pit to the building site.

We built A-frames on the block foundation, and then moved them into position using levers, blocks, ropes and pulleys. The first A-frame was one-third the way up when the contractor happened to arrive to get his backhoe. He finished raising that one into position. After guying the first A-frame into position, it was used to lift the others upright. We celebrated Thanksgiving by having electricity and by Christmas we had baseboard heat. A mild winter with little snow allowed us to park the car off the Highway and backpack in supplies as they were needed.

By spring, the house was essentially completed. Following the construction of our home, I designed and built a sawmill from which I sawed lumber from our own logs to build other outbuildings for a shop, and machinery and aircraft storage.

While taking a winter walk in the early 1970s, I noticed that the flat, mostly level benches extending to the northeast and southwest from the house could be linked together by filling in the low drainage between them. The idea for an airstrip was born. I began the slow task of moving earth from the back on the upper side of the dip to the low spot using a one and a half yard front loader. By the time I was finished the toe of the fill was twenty feet deep. Of course, I also had to clear all the lodge pole pine (selling most of the trees for fence posts) from the 2500-foot runway and dig out the stumps. I had acquired a road grader that my mother had used in her road contracting and mining business in California, allowing me to make a smooth finish on the strip.

Meanwhile, in 1974 I started to build my first airplane, a tandem seat Wendt Traveler with an eighty-five horsepower Continental engine. The maiden flight was on October 18, 1977. Butchie was a big help in the plane’s construction and was not a bit hesitant to go up with me. She would say “I know how well built it is because I was there helping.” The required fifty hours of proving flight time was accumulated in 1978. I was back to real flying again, and from my own private airstrip to boot!

I always needed to have a winter project. Next, I bought a wooden wing Mooney, rebuilt it and sold it. Following that, I built a Fisher Classic biplane. A Rotax engine originally powered it. This was only twenty-seven horsepower, not enough at this elevation, so I replaced it with half of a VW engine that put out thirty-five horsepower. I only flew the plane once, just down the runway.

My next project was a Fokker Triplane, like the one flown by the Red Baron in World War One. There were no plans as such for a full-scale aircraft, so I used the model airplane plans from the Cleveland Model Airplane Company and scaled up all the measurements to the full dimensions of the real aircraft. As a child I had built aircraft models from this company’s plans and knew them to be accurate. Once again, I powered the plane with a half of a VW engine. Although I completed the Fokker, it has never flown.

Other winter projects have included building a dump truck, a four-wheel drive golf cart and a water well drilling rig. During the summers I have worked to clean up and burn bug killed pine trees, using the logs to make corduroy passages over swampy ground.

Butchie and I were avid hunters in Alaska and the lower forty-eight. We have several trophy big horn sheep and mountain goat heads displayed in our home. Butchie likes to brag that she got the largest big horn. I still go elk hunting and got a bull nearby last fall (2006).

Ben William Ryan passed away peacefully July 26, 2017 at the Montana Veteran’s Home in Columbia Falls with his loving wife Agnes, “Butchie” and friends at his side.